This article by Linda Emerick studies young gifted people who have pulled themselves through periods of underachievement. It details the main areas that these students felt were crucial in being able to reverse the pattern of underachievement in their lives. The results suggest that educational interventions focused on areas of student interest may be particularly effective.

Author: Emerick, L. J.

Publication: Gifted Child Quarterly

Publisher: National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC)

Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 140-146

Summer 1992

ABSTRACT

Underachievement among the gifted has been a focus of research, for over 35 years. With few exceptions, studies of interventions for gifted underachievers have demonstrated only limited success. This study investigated factors which had influenced the reversal of the underachievement pattern in 10 gifted students, ages 14 to 20, who moved from chronic underachievement to academic success. Results indicated six factors were influential in reversing poor school performance. There was evidence that some gifted underachievers may respond well to interventions incorporating educational modifications which focus on individual strengths and interests.

Putting the Research to Use

Parents and teachers working with students to reverse the underachievement pattern may wish to consider a number of factors. Results from this study indicate that it is important to identify the underachiever’s areas of strength and talent. Personal interests can motivate the student to learn and provide an avenue for learning various skills related to school success. Providing appropriately challenging curriculum during the period of underachievement also appears to be important. School personnel should consider gifted underachievers candidates for gifted education services and/or advanced classes. The underachievers in this study also seemed to respond well to parents and teachers who had high expectations, provided calm and consistent guidance, and maintained a positive, objective regard for the student. The study’s findings indicate that academic underachievement can be reversed as a result of modifications on the part of both the student and the school.

Academic underachievement has been a persistent area of concern for educators, parents, and students for at least the past 35 years. The gifted underachiever has been described as “one of the greatest social wastes of our culture” (Gowan, 1955, p. 247). Beyond the social cost, however, there are personal wastes as well — opportunities for advanced educational experiences and personal development are thwarted by academic underachievement. Today, there is no problem more perplexing or frustrating than the situation in which a bright child cannot or will not perform at an academic level commensurate with his or her intellectual ability.

The gifted child who is an academic underachiever may suffer from more than poor grades and the disapproval of parents and teachers. Unfortunately, if performance in school is deemed inadequate, the child may also perceive himself or herself as inadequate in other kinds of learning experiences. As these unpleasant experiences continue, a negative attitude toward school, self, and learning in general may result, and poor motivation habits may develop (Covington, 1984). According to Bloom (1977), “There is considerable empirical support for relating the individual’s perception of his inadequacy in school learning to the development of related interests, attitudes, and academic self-concept” (p. 197). The strengths and potential of gifted underachievers are often ignored or go unrecognized. As a result, the student may be denied appropriate educational opportunities and his/her curiosity and love of learning may be extinguished.

Considerable research has been devoted to understanding and helping the gifted underachiever. Studies have focused on identifying characteristics unique to this group, isolating causal factors, and developing effective interventions to reverse the underachievement pattern. In spite of the number of studies conducted in these areas, the picture of the underachiever which emerges is complex and often contradictory and inconclusive . With few exceptions, interventions reported by researchers have failed or have had limited success (Dowdall & Colangelo, 1982). It has been suggested that reversing the underachievement pattern among the gifted has not progressed because researchers failed to understand the individual sufficiently and failed to investigate systematically all aspects of the problem (Lowenstein, 1977).

One area of academic underachievement not investigated previously is the gifted student with a record of chronic underachievement who has been able to reverse the pattern without apparent attempts at intervention by parents or educators. Although experts such as Bricklin and Bricklin (1967) have confirmed the existence of such students, no studies have focused specifically on identifying characteristics of this group and understanding the factors that brought about academic success.

In order to understand the process of the reversal of the underachievement pattern, it is necessary to gain some understanding of the meaning the individual attaches to achievement-oriented behaviors or to the factors contributing to such behaviors. Discovering those factors that may contribute to above-average performance in school entails investigating bright children and young adults who have moved from patterns of underachievement to academic achievement. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to identify those factors the gifted underachiever perceived as contributing to the reversal of the academic underachievement pattern.

Method

Subjects

The subjects who participated in the study were selected using purposeful sampling. Notices were sent to state and district coordinators of gifted education asking them to nominate students who met the following criteria:

1. The student demonstrated intellectual giftedness as evidenced by any of the following: standardized achievement test scores (90th+ percentile), scores on tests of general aptitude (125+ IQ), or other objective and subjective indicators of potential for well-above-average academic performance.

2. The student demonstrated a sustained period of general academic underachievement (2 years or longer ) as supported by evidence of average or below-average academic performance. Evidence included test scores, grades, and observations by education professionals.

3. The student demonstrated a sustained reversal of the academic underachievement pattern (1 year or longer) as evidenced by above-average academic performance. Indicators of academic achievement included test scores, grades, academic awards and honors, and observations of education professionals.

The age range of students who were nominated for the study was carefully determined in order to (a) ensure that students were “close” in time to the period of academic underachievement and the subsequent reversal of the underachievement pattern and (b) increase the probability that, developmentally, the students would be able to reflect upon and articulate their perceptions of various aspects of these events (Harris & Liebert, 1987).

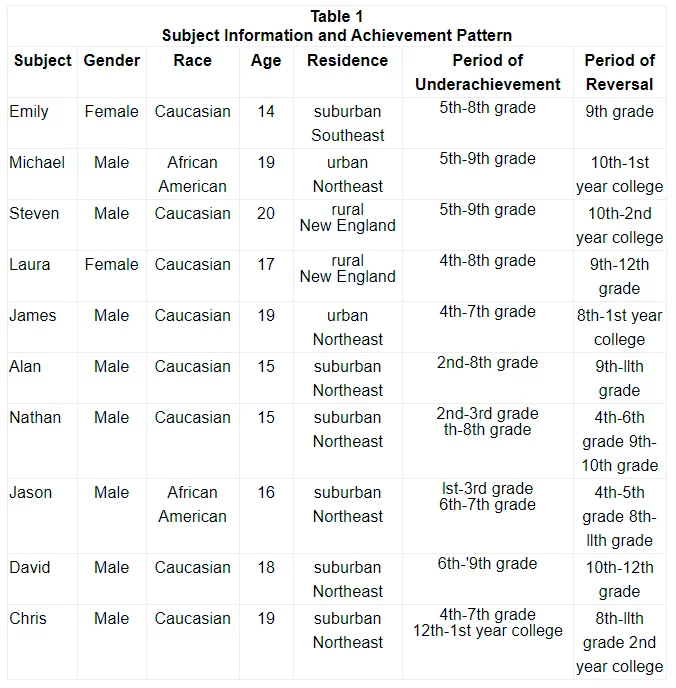

Once a group of students had been nominated, 10 individuals were selected. Variability among the participants helped strengthen the explanatory power of the data gathered. The students were 10 young adults, ages 14 to 20, from northern New England, the Northeast, and the Southeast regions of the United States. The group was made up of 2 females and 8 males and included 2 Afro-Americans and 8 Caucasians of varying socioeconomic backgrounds. The subjects came from urban, suburban, and rural settings. Table 1 summarizes the general demographic and achievement history of the subjects.

Data Collection

There were two phases in the collection of data. Phase one involved gathering information about each subject regarding biographical background, evidence of above-average intellectual ability, and history of academic performance. This phase was accomplished by the use of questionnaires for parents, nominating educators, and the subjects; follow-up written and telephone communication; and the collection of related school records for each participant. The data collected in this phase were used to verify that criteria for participation in the study were met and to aid in the development of the questionnaire and interview guide used in phase two. Phase two of data collection involved gathering information directly from the 10 subjects. Two methods were used: written responses to an open-ended questionnaire and in-depth interviews with each subject. The written questionnaire provided information that aided in the development of interview questions and provided between-method triangulation of subjective perceptions when used in conjunction with interview data. The interview guide approach (Patton, 1987) was used in conducting interviews with each subject. Interviews were conducted over a 4-month period with individual sessions averaging 2 to 3 hours per subject. One to three sessions with each student were conducted. The number of sessions was determined by the point at which data saturation was attained.

Data Analysis

The goal of the analysis was to discover common themes in the written and oral responses of the subjects, to organize this information, and to draw conclusions about this population which could be verified and lead to further action. The data from the questionnaires and interviews were analyzed using a three-step data reduction process to code perceptions, organize the codes into themes, and identify themes held in common by the 10 subjects.

Results

Analysis of questionnaire responses and interview data revealed six themes or factors consistently addressed by all 10 subjects in relation to reversal of the academic underachievement pattern. These factors were labeled as: (a) out-of-school interests/activities, (b) parents, (c) the class, (d) goals associated with grades, (e) the teacher, and (f) self. Although all six factors were perceived as important to the 10 subjects, there were different opinions regarding the level of importance except for factors 5 and 6. These two factors were identified by all the subjects as primary in importance. All six factors and the perceived role of each in helping the subjects achieve academic success are described below. Names of the subjects have been changed to ensure anonymity.

Out-Of-School Interests/Activities

All 10 students had long-standing out-of-school interests and activities of a decidedly intellectual or creatively productive nature. For example, Alan had constructed a science laboratory in the basement of his parents’ home at age 8 and had added to it and continued to use it extensively for 7 years. Jason wrote musicals in fifth grade which were produced and performed by the high school drama club. He had also organized a dance troupe of teenagers who performed professionally. David started his own computer business in junior high, designing software and netting $3,000 his first year. Laura had a wide range of interests and conducted her own investigations into various topics out of school. In every instance, the students were engaged in these and similar types of activities during and after the periods of chronic academic underachievement in school. The students believed that their interests and hobbies helped them achieve academic success in four ways:

1. The outside interest provided an “escape” from what the students determined to be less-than-favorable school situations. As Nathan explained, “[The area of interest] is an outlet for your frustrations…you can’t just focus on school. There is more to life than school…I mean, when I started getting into [photography, computers], I think that helped my school [performance], too, ’cause it gave me something to concentrate on besides school.”

2. The area of interest or activity provided the subject with a sense of self-worth and success in the face of academic failure. According to Chris, this was something he sometimes believed “was the only thing I knew how to do well. It kept me going.” He believed performing in the school band and creating his own jazz group corresponded with academic improvements in school because it allowed him some degree of control over his life as well as being a constructive, creative endeavor.

3. Out-of-school interests were seen as an avenue for maintaining a love of learning and increasing the skills necessary to become an independent learner. Steven believed his educational program did not always provide a challenge, as a result of both the curriculum and his own in-school difficulties. His interests in reading, math, and computer science filled the gap he thought existed–“I could find my own enrichment. School does not need to be particularly enriching to me now.”

4. Out-of-school interests and activities helped the subjects identify in-school learning experiences which were meaningful to them. In other words, school and academic achievement became relevant because of its usefulness in the area of personal interest. For example, Jason saw his strong interest in drama, “aspects of feelings and people,” and reading as enabling him to perform well in an English class and experience academic success. He had always seen himself as a “people person” and found himself interested in this class because he enjoyed discussing the literary characters and what motivated their actions, topics which related directly to his own playwriting activities.

Parents

The students perceived that their parents had a positive effect on their academic performance. Parental impact appeared to have been primarily of a psychological nature, relating to the students’ feelings of self-worth. Parents were perceived as contributing to their academic success in three ways:

1. The parents had directly or indirectly approved of and supported the children’s out-of-school interest. In general, the students’ regarded this support as an indication that their parents valued them for more than their achievements in school. They also believed their parents hesitated to use these interests as a means of changing their behavior. Although a student might have to spend less time on his or her out-of-school interest area in order to catch up on assignments or to study more, the interest area was never withheld as a form of punishment for poor performance in school.

2. The students indicated that their parents had maintained a positive attitude toward them, even in the face of academic failure. When Nathan found himself in academic trouble “that was really discouraging. . . [my parents] really helped me get through some tough times. . . helped me keep it in perspective.” Nathan and the other students believed their parents had not been discouraged and had not seen the underachievement pattern as a permanent situation.

3. Parents were perceived as having remained calm, consistent in behavior, and objective during the underachievement situation. The students also believed the parents had eventually placed the responsibility for performance in school directly on them. The students reported initially resisting their parents’ attempts to remain calm and objective. Eventually, however, they felt the shifting of responsibility had had a positive effect on their academic performance.

The Class

All of the subjects in this study identified specific characteristics of academic classes as contributing to the reversal of academic underachievement. These characteristics included the following:

1. The class that had a positive influence on the student provided opportunities for intellectual challenge and advanced studies. This type of class was frequently described as “fun.” For many of the students, the “fun” classes were more difficult and often eliminated basic course content that the students had previously mastered. They were encouraged to progress through material at a faster rate than in classes where they did not perform as well. Alan described finally being successful academically when he was allowed to “skip right over [basic science] and take college prep Biology. That part of high school worked really well for me.” In addition, these classes were perceived as providing intellectual and creative challenges by “going just over the students’ heads academically.” All of the students described successful classes as more complex. It was in these classes that the gifted underachieving students began to strive to improve academic performance.

2. The class that provided opportunities for independent study in areas of interest was believed to promote academic excellence. The students perceived assignments as “easier to complete” when they were part of a project the student had selected. Laura became excited about learning while in a high school science class “because you were expected to go on your own a bit [in learning] … I liked going off and working on something that way.” Other students found the opportunity to participate in independent studies invaluable since many of the skills related to their projects and interests outside the school setting.

3. Classes that included opportunities for student discussion as part of instruction were important to these students. All 10 expressed a need for the personal involvement that discussions provided, and they believed the discussions made the content more interesting and relevant.

4. Class activities and assignments motivated the students to excel when they were “real” or relevant to the student. The subjects believed they exerted more effort in their studies when they had the opportunity to apply skills and content they had learned. Emily had failed science courses on a regular basis until she enrolled in a class that emphasized hands-on experiments. She believed she performed at a higher level because she was “doing what real scientists do…not just answering questions in a book and taking a test.”

5. Classes in which the students were successful academically focused on the process of learning as well as the final product in the assessment of achievement. The subjects were especially delighted with classes in which traditional methods of grading were minimized. In turn, they believed they learned more and were more successful in classes where opportunities for feedback and revision were provided.

Goals

The students agreed that grades and similar indicators of academic achievement held little or no meaning and importance for them. Most remembered earlier efforts to succeed academically as motivated primarily by a desire to please their parents and win general approval. One way in which the students perceived themselves as able to reverse the underachievement pattern was through developing goals the attainment of which was both personally motivating and directly related to academic success.

The goals chosen to be paired with academic achievement varied from one student to another. Entry into a particular field of study such as engineering or into a specific college or university was selected by some; more global aspirations were chosen by others. Michael, a young Afro-American, chose to succeed academically because his “goal was to break the stereotype of the Black teenage male who can’t make good grades. And I succeeded.” Other students believed they could improve their self-image or increase the amount of time they had for their other interests by improving their classroom performance: “You put a bit more time into school, you see. Otherwise, it creates lots of friction, you’re tense, and it’s counterproductive. Now I actually have more time to work on my own because there’s no more hassle.”

The Teacher

The students who participated in this study believed a specific teacher was the single most influential factor in the reversal of the underachievement pattern. All the subjects thought that although the previous four factors were crucial to their academic turnaround, it was the actions of and respect for a particular teacher that had the greatest positive impact. According to them, the teacher who motivated each of them to learn and excel in school displayed the following characteristics:

1. He or she cared for and sincerely liked the student as an individual. Interestingly, “caring” teachers were described by the students as displaying a wide variety of characteristics. Some caring teachers were described as soft-spoken and able to empathize with the student who was performing poorly in class. Others described gruff, abrupt, no-nonsense individuals as equally caring. According to James, his influential teacher was “very callous, really; but he just drove us to learn. I think his callousness was just an exterior. I know he really liked us.” The common factor in the descriptions of the teacher among all subjects was the belief that he or she was concerned about the individual.

2. The teacher was willing to communicate with the student as a peer. The students described instances in which they “could really talk” to the teacher about ideas, topics of interest, and personal concerns. The teacher was viewed as an equal as well as a facilitator for learning.

3. The teacher was believed to be enthusiastic and knowledgeable about the topic taught and demonstrated a personal desire to learn more. All students reported instances in which they were motivated by a teacher’s love for a subject and as a result, performed at above-average levels in subjects they did not like. As one student stated, “If the teacher is enthusiastic enough and knows her stuff, it’s just contagious.”

4. The influential teacher was perceived as not being “mechanical” in methods of instruction. Usually, the student reported being directly involved with the teacher during the learning process. Student participation was seen as a top priority of the teacher. In addition, the teachers incorporated a wide range of resources and strategies beyond the textbook and lecture. One teacher was described as being a positive influence because she used videotapes to help bring the study of Irish poetry to life. The students analyzed the poems and the films. Another teacher was remembered for the unique items he brought from home and his travels to illustrate concepts in a science class. The students believed these behaviors indicated flexibility on the part of the teacher.

5. The teacher was perceived as having high but realistic expectations for the academically underachieving student. The students reported the influential teachers knew the students well enough to be able “to go over my head academically and make me climb the rope to that higher level.”

Self

Although it was not selected by the students as the most influential factor, a significant change in the individual’s concept of self was viewed as necessary for the reversal of the underachievement pattern. In particular, each student believed he or she had undergone such a change and that without this change, the other factors would have had little or no personal impact. The perceived changes in attitude toward self included the following:

1. The student believed he or she developed more self-confidence and a positive attitude toward the underachievement situation. Some believed their confidence grew from a series of small successes experienced in and out of school. Other students believed they had overcome the detrimental effects of perfectionism in order to gain the confidence to succeed.

2. The student began to perceive academic success in school as a source of personal satisfaction and a matter of personal responsibility. The students expressed the belief that they had previously seen academic achievement as a way to please others. Once the process of learning in school became a personal matter, they believed they were ready to reverse the underachievement pattern. In turn, the sense of personal pride in their success led to the perception that responsibility for improved performance rested with the student.

3. The students believed they had gained the ability to reflect on and understand factors that may have contributed to the underachievement pattern. They were not certain what had brought about the ability to “see the whole picture” but viewed this as very important.

Conclusions and Discussion

This study examined gifted students’ perceptions of factors which contributed to the reversal of academic underachievement. Six factors were identified by the students as having a positive impact on their academic performance: out-of-school interests, parents, goals associated with academic achievement, classroom instruction and curriculum, the teacher, and changes in self. Although the factors differed to some degree from those found by-other studies, the number and nature of them support the idea that underachievement and its reversal is complex and unique to each child (Rimm, 1986; Whitmore, 1980).

The gifted underachiever who had reversed patterns of academic underachievement in this study exhibited characteristics also associated with the highly creative and gifted individual: independence of thought and judgment, willingness to take risks, perseverance, above-average intellectual ability, creative ability, and an intense love for what they were doing (Renzulli, 1978; Torrance, 1981). The level of achievement occurring outside the classroom indicated that school was frequently the only place academic and creative achievement were not taking place. The students also expressed a need for personal involvement with and respect for the abilities of those directing their education.

This study suggests that reversing the underachievement pattern may mean taking a long, hard look at the underachiever’s curriculum and classroom situation. The responses and actions of the students in this study indicate that when appropriate educational opportunities are present, gifted underachievers can respond positively. This supports the findings of Whitmore (1980) and Butler-Por (1987) who discovered that when the gifted child is educated in the “least restrictive environment” in the school setting, underachievement is minimized. Attempts should be made continually to upgrade content and skills, minimize repetitive and redundant lessons, and provide educational challenges in the regular classroom, even when it appears remediation is necessary.

The educational experiences in which the students improved or performed well were related to their out-of-school interests and were characteristic of learning situations deemed appropriate for the gifted: “real world” application of learning, minimal repetitive assignments, use of higher levels of critical thinking, and opportunities for self-initiated and self-directed learning, to name a few (Betts, 1991; Renzulli & Reis, 1985; Treffinger, 1986)). While not all the classes in which the students began to improve academically were labeled “classes for the gifted,” they bore the characteristics of those in which the curriculum and instruction had been differentiated to meet the needs of the gifted learner.

Factors not previously researched as contributing to the reversal of the underachievement pattern were revealed in the study. The students’ out-of-school interests and the role of particular teachers were regarded as major factors in the improvement of academic performance and increase in appreciation for learning in the school setting. Few interventions described in the literature have attributed academic success among underachievers to having very strong interests in other areas. Although it has been widely assumed that the teacher plays a crucial role in the reversal of underachievement, few research studies have examined the specific role of the teacher and his or her personal characteristics as the basis for developing effective interventions. This study suggests that the role of the teacher and the effort to link the underachiever’s areas of interest to academic pursuits need to be investigated further. The studies of effective role models and mentors, many of whom are teachers, may be especially helpful as a guide to further study.

The in-school performance pattern of the students in this study suggests that the reversal of underachievement may be lengthy and marked by uneven progress. The students expressed the expectation that there would be “steps backward” as they moved toward academic success, arid records of school performance supported their perceptions.

Implications

The findings reported here reflect the perceptions of one group of students who moved from patterns of academic failure to academic success. Although the results should not be generalized widely, this study does suggest steps that may be taken to help gifted underachievers with strong creative interests and involvement. These include the following:

1. Identify the underachiever’s strengths and interests as well as areas that need improvement. Through recognizing and emphasizing the characteristics of the child that relate to his or her giftedness, educators and parents can see the child as more than a problem waiting to be “fixed.” This approach focuses on the positive behaviors of such students and communicates positive expectations about behavior in the academic setting. Knowledge of the underachiever’s strengths and interests can also help pinpoint abilities which may not be evident from the student’s test scores or school performance. The experiences of the subjects in this study indicate that schools may fail to investigate these indicators of potential or may identify these indicators solely as problems rather than examples of motivation and ability to learn.

2. Integrate the strengths and interests of the child with academic performance in school. The students in this study believed that when they could perceive a relationship between their own interests and learning experiences in the classroom, they were motivated to perform well.

3. Provide opportunities for gifted underachievers to receive special educational programming in gifted education. The students in this study were often denied access to gifted programs which might have been beneficial in the development of their abilities as independent learners. Those students who were able to participate in such programs found the advanced opportunities for independent studies valuable in maintaining their desire to learn.

4. Include parents of gifted underachievers in determining the educational needs of their children. The importance of parental support and the need for positive action and attitudes makes it imperative that parents be informed of the unique needs of their child, particularly as related to gifted behaviors, and the role they can play in the reversal process.

5. Teachers of gifted underachievers should be encouraged to advocate for the underachiever. In fact, according to these students, teachers at all grade levels play a major role in reversing underachievement. It appears that teachers who are seen as the most willing to help and are perceived as the most effective in learning situations exhibit many of the same characteristics as the subjects–love of learning, task commitment, personal involvement with the subject matter and the students.

6. Be patient. It will take time to reverse the patterns of underachievement. Hopes for the development of an intervention which offers immediate and permanent reversal of the underachievement pattern may be unrealistic and may inhibit the search for effective measures. Because of the many factors which can influence the onset and the reversal of underachievement, we must expect uneven progress and periodic setbacks when helping the gifted underachiever. What is heartening about this study, however, is the evidence that some forms of academic underachievement can indeed be reversed.

References

Betts, G. T. (1991). The autonomous learner model for the gifted and talented. In N. Colangelo & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (pp. 142-153), Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bloom. B. (1977). Affective outcomes of school learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 32. 193-198.

Bricklin, B., & Bricklin, P. (1967). Bright child, poor grades. New York: Delacorte.

Butler-Por, N. (1987). Underachievers in schools: Issues and intervention. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Covington, M. V. (1984).The self-worth theory of achievement motivation: Findings and applications. Elementary School Journal, 85, 5-20.

Dowdall, C. B., & Colangelo, N. (1982). Underachieving gifted students: Review and implications. Gifted Child Quarterly, 26, 179-184.

Gowan, J. C. (1955). The underachieving child: A problem for everyone. Exceptional Children, 21, 247-249, 270-271.

Harris, J. R., & Liebert, R. M. (1987). The child: Development from birth through adolescence. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lowenstein, L. F. (1977). An empirical study concerning the incidence, diagnosis, treatments, and follow-up of academically underachieving children. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 166 922)

Patton, M. Q. (1987). Qualitative evaluation methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Renzulli, J. S. (1978). What makes giftedness? Re-examining a definition. Ventura, CA: N/S-LTI G/T.

Renzulli, J. S., & Reis, S. M. (1985). The schoolwide enrichment model. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Rimm, S. (1986). Underachievement syndrome: Causes and cures. Watertown, Wl: Apple Publishing.

Torrance, E. P. (1981). Emerging concepts of giftedness. In W. B. Barbe & J. S. Renzulli (Eds.), Psychology and Education of the Gifted (3rd ed.) (pp. 47-54). New York: Irvington.

Treffinger, D. J. (1986). Fostering effective, independent learning through individualized programming. In J. S. Renzulli (Ed.), Systems and models for developing programs for the gifted and talented (pp. 429-460), Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Whitmore, J. R. (1980). Giftedness, conflict, and underachievement. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Permission to reprint this article has been granted by Gifted Child Quarterly, a publication of the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC). This material may not be reproduced without permission from NAGC.

Disclaimer: The appearance of any information in the Davidson Institute’s Resource Library does not imply an endorsement by, or any affiliation with, the Davidson Institute. All information presented is for informational and archival purposes only. The Davidson Institute bears no responsibility for the content of republished material. Please note the date, author, and publisher information available if you wish to make further inquiries about any republished materials in our Resource Library.

Comments