Deeper Dive

Centripetal Agonies concerns itself with the distances, beauties, shortcomings, confinements, and transcendences of language. Around April 2023, when I began the process of writing a historical novel, I was taken aback by the strange interrelations and associations of topics I had not thought to be connected: in beginning first to revolve pieces around animal studies, the narratives would over time accumulate with notions of environmentalism, social ontology, and psychology, including precisely how these topics intertwine. Consequently, in my analysis of history, I engrossed myself within a wide array of studies, including topics like religious traditions and hysteria, quantum entanglement and the early development of physics, the deciphering of early modern English, political systems, public health, astrology, and the development of philosophy across time. Utilizing archives and databases, this research was carried out heavily through the exploration of first-hand documents, including letters, etchings, diaries, journals, photographs, colloquial dictionaries, and regional news, all dating back as far as the early 1600s, in an attempt to relate each singular experience I found into an encompassing narrative—one that presented reality as a collective, constantly fluctuating. The major implications of the portfolio develop in the interweaving and deconstructing of several enduring conditions with regard to tragedy and our past: the inheritance of presupposed societal dynamics, the elusiveness of objectivity, and the constant, withstanding barrier of communication.

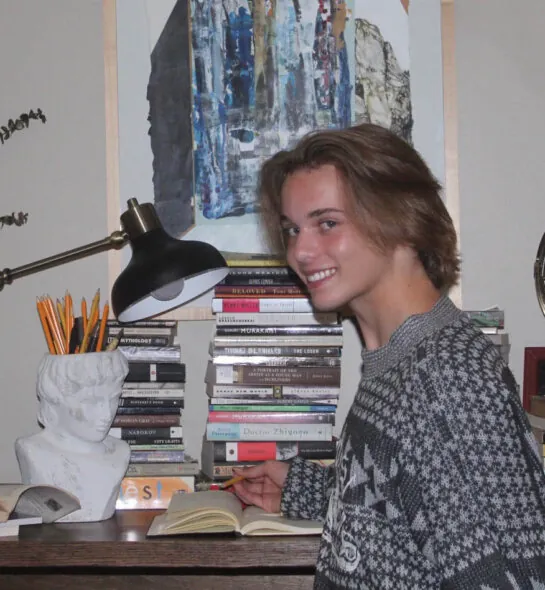

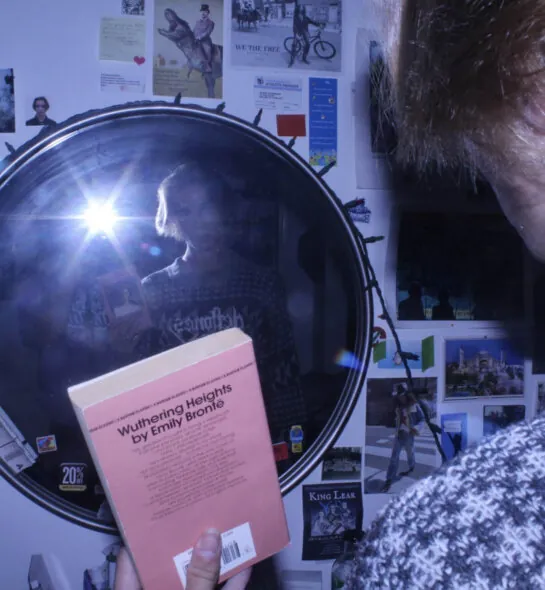

Ludwig Wittgenstein declares in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” The failure of language is the problem unraveling tangentially to societal atrophy throughout the portfolio, notably in the abstraction of sentience from animals. It is observed chronologically through Old Testament narratives, the Great Plague of London, post-Spanish-American War Spain, and Mexico before the Second World War. In challenging the distance of language and attempting to bypass constructed ideas of narration and dialogue—to articulate the inexpressible—there was a necessity to push the form of writing past its limits. This materialized in the use of radical techniques like polyphonic narration, maximalism, fragmentation, and heteroglossia, allowing in every expanding sentence the ability to entangle, to gather with debris, and to take singular moments and prod at them—pulling apart each individual fiber of an event, only to stitch them back together in an entirely different form. As a result, the interweaving structure throughout became surreal: sentences spanned pages, perspectives rapidly oscillated, abstractions became concrete. While writing these pieces I constantly surrounded myself with stacks of heavily annotated works, novels and nonfiction that often experimented structurally, such as those of post-modernists like Thomas Bernhard, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, W.G. Sebald, and Jose Saramago. Because each story was conceived in philosophical thought, I addressed plot and structure by asking myself questions or actualizing the questions of others—often relating to the ontological and sociological realms of metaphysics and the philosophy of language—and would allow these queries to be answered in a narrative form, often assuming the tangible (and intangible) forms of strange symbols and barreling syntax. As a result, the pieces continually, in their themes and propositions, respond to and expand upon the concepts established by Jean Baudrillard of simulacrum and implosion of meaning, Jacques Derrida’s philosophies of deconstruction and zoopoetics, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s expressed inexpressible, and the subversion and rejection of the Cartesian model as expressed by Jacques Derrida, Charles Sanders Peirce, Peter Singer, Jeremy Bentham, and Jacques Lacan. While I had no formal mentoring or counseling from teachers, this project, like the history I write of, is one that expanded with every new perspective I encountered, and it would never have amalgamated into its final form without the conversations had with close friends and family, of which were absolutely invaluable to my process.

This project is so exceedingly ambitious in its scope because it asks for fundamental re-evaluations in the way we observe our singular and collective histories and realities. A key proposition of Centripetal Agonies is that models of philosophy, developed as early as the 1600s—primarily Rene Descartes’ concept of automata—have anticipated the arbitrary ethics and subjugating compartmentalization highlighted in modern zoo and factory farming cultures. In making such a claim, readers are therefore compelled to extend such criticisms of categorization & bias to the hierarchical structures within their own lives. There is an insistence on a radical expansion of narrative throughout, constantly resisting brevity and allowing for superfluities and uncertainties as a way of questioning our imperfect relationship with storytelling, and as a way of surpassing the walls that language can confine us in—with all the boundless possibilities that arise in this transcendence. In fundamentally rethinking narrative, we investigate our pasts, and how the limits of singular perspectives have perhaps altered and distorted our notions of chronicled events. In every entanglement, in every inarticulable moment, Centripetal Agonies allows us to consider the future by remembering a more encompassing past; as Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, “for here there is no place / that does not see you. You must change your life.”