Author: Amend, E. et al.

Publications: Gifted Child Today

Publisher: SAGE Journals

Volume: Vol. 32, No. 4

Year: Fall 2009

Joey loved nature more than anything else. As a 4-year-old, he knew more facts about climate zones, geography, and geology than most high school students. His intellectual curiosity was astonishing. He often devised his own scientific experiments—at home and at school. Joey’s advanced vocabulary, enjoyment of being with older children, and high level of motivation were noted by his parents and preschool teachers. And yet, Joey’s socialization skills did not match his highly developed abilities. For example, he failed to recognize how others felt, had unexpected rages without clear provocation, and often spoke in a formal and pedantic manner that turned others off. He was clumsy, which affected his physical play with other children. Sensory issues and meltdowns also were present. Questions arose: Gifted and quirky, Asperger’s Disorder, or both?

The Disorder

Asperger’s Disorder is a pervasive developmental disorder on the autism spectrum. It is characterized by severe deficits in age-appropriate social interactions and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior or interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). There is no doubt that a gifted child can have Asperger’s Disorder and that this combination has a profound impact on both social interactions and schooling (Amend & Schuler, 2004; Cash, 1999; Neihart, 2000).

A gifted child with a disability like Asperger’s Disorder (or a learning disability or Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder) is referred to as a twice-exceptional child. Programming for twice-exceptional students is difficult because their abilities often straddle both ends of the bell-shaped curve, with strengths and weaknesses needing to be addressed in order for interventions to be successful. Even though twice-exceptional students are in the minority, identifying these students presents a significant challenge because gifted children who are misunderstood can be easily misdiagnosed by those not aware of the typical characteristics of gifted children (Hartnett, Nelson, & Rinn, 2004; Lovecky, 2004; Webb et al., 2005).

The Implications

All-too-often, well-meaning individuals urge parents to seek referrals for psychological evaluation without considering or understanding the typical characteristics of gifted children or the impact of intellectual ability on behavior and relationships. In turn, clinicians receiving such referrals also may fail to assess the implications of giftedness when exploring potential diagnoses like Asperger’s Disorder.

The interested reader is referred to the book Misdiagnosis and Dual Diagnoses of Gifted Children and Adults (Webb et al., 2005) for a thorough discussion of diagnostic issues among the gifted population.

Joey’s teachers knew that he was a smart little boy, but their focus was on his negative classroom behaviors. A Preschool Individualized Education Program (IEP) was developed that emphasized managing his sensory issues and meltdowns resulting from his obsessive nature and rigidity about rules. Occupational therapy and social work, as well as services for the family, were incorporated into Joey’s IEP. Although these services were helpful, Joey’s parents realized the paradoxes of their son and sought help for his intellectual needs and perfectionist tendencies. They contacted a counselor/consultant who specializes in working with gifted children to help them with their advocacy. The prereferral process began.

The Process

Like Joey, a gifted child’s abilities and talents must be considered not only in the referral process and evaluation, but also in the prereferral intervention phase. Prereferral is the process of obtaining a thorough understanding of a gifted child or adolescent by examining the frequency, severity, and duration of any presenting behaviors and whether any are problematic. Current functioning is the focus of the prereferral process (Boland & Gross, 2007). Interviews with parents or guardians and the child, as well as instruments that provide data on the functioning of the child, help to determine appropriate prereferral interventions. These may include best practices found in gifted education: daily challenge in specific areas of talent; regular opportunities to be unique and work independently in passion and talent areas; various forms of acceleration based on needs; opportunities to socialize and to learn with like-ability peers; and differentiated instructional delivery, including pace, amount of review and practice, and organization of content presentation (Rogers, 2007). Without appropriate prereferral interventions, opportunities to have a profound positive impact may be missed. By adjusting the educational environment and curriculum in the prereferral stage to meet the unique learning needs of the gifted student, positive changes may be seen.

The Dilemma

When the gifted child’s intensity is combined with a classroom environment and curriculum that do not meet his educational needs, his behavior is more likely to be viewed as different (Baum & Owen, 2004; Cross, 2004) and, perhaps, pathological. As a result, the gifted learner with a unique interaction style may be initially mislabeled (and eventually misdiagnosed) when his educational needs are not met. This mislabeling can lead to inappropriate interventions that result in more—rather than less—problems in the classroom (Eide & Eide, 2006). Conversely, dramatic positive changes can be realized when the gifted child’s abilities and unique characteristics such as intensity are taken into account when developing prereferral strategies, during the evaluation process, and when identifying postevaluation interventions.

For Joey, the prereferral process included an examination of all health records and past testing, interviews with Joey and his parents, teacher input, and observation of his current level of functioning. It was apparent that Joey demonstrated many of the behaviors characteristic of both giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder. When Joey started kindergarten in a private school with behavioral consultation services, the gifted counselor/consultant recommended a variety of acceleration, enrichment, and different grouping opportunities to meet his cognitive and social needs. It also was recommended that Joey’s parents enroll him in a research study on autism at a nearby center known for its work with autism spectrum disorders. It was there that Joey was formally diagnosed with Asperger’s Disorder. Fortunately, Joey’s highly gifted intellectual abilities also were recognized. Suggestions by the center dovetailed those given in the prereferral process to develop Joey’s strengths while accommodating his weaknesses.

The Instrument

Although the literature on Asperger’s Disorder is replete with many references to high ability/giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder (e.g., Attwood, 2007; Bashe & Kirby, 2001; Grandin & Duffy, 2004), there is, at this time, only one instrument that delineates giftedness and characteristics of Asperger’s Disorder. BurgerVeltmeijer (2008) of the Netherlands created the Dimensional Discrepancy Model GFT + ASD (DD-Checklist) to help psychologists observe the characteristics of gifted-like manifestations versus Asperger’s Disorder-like manifestations.

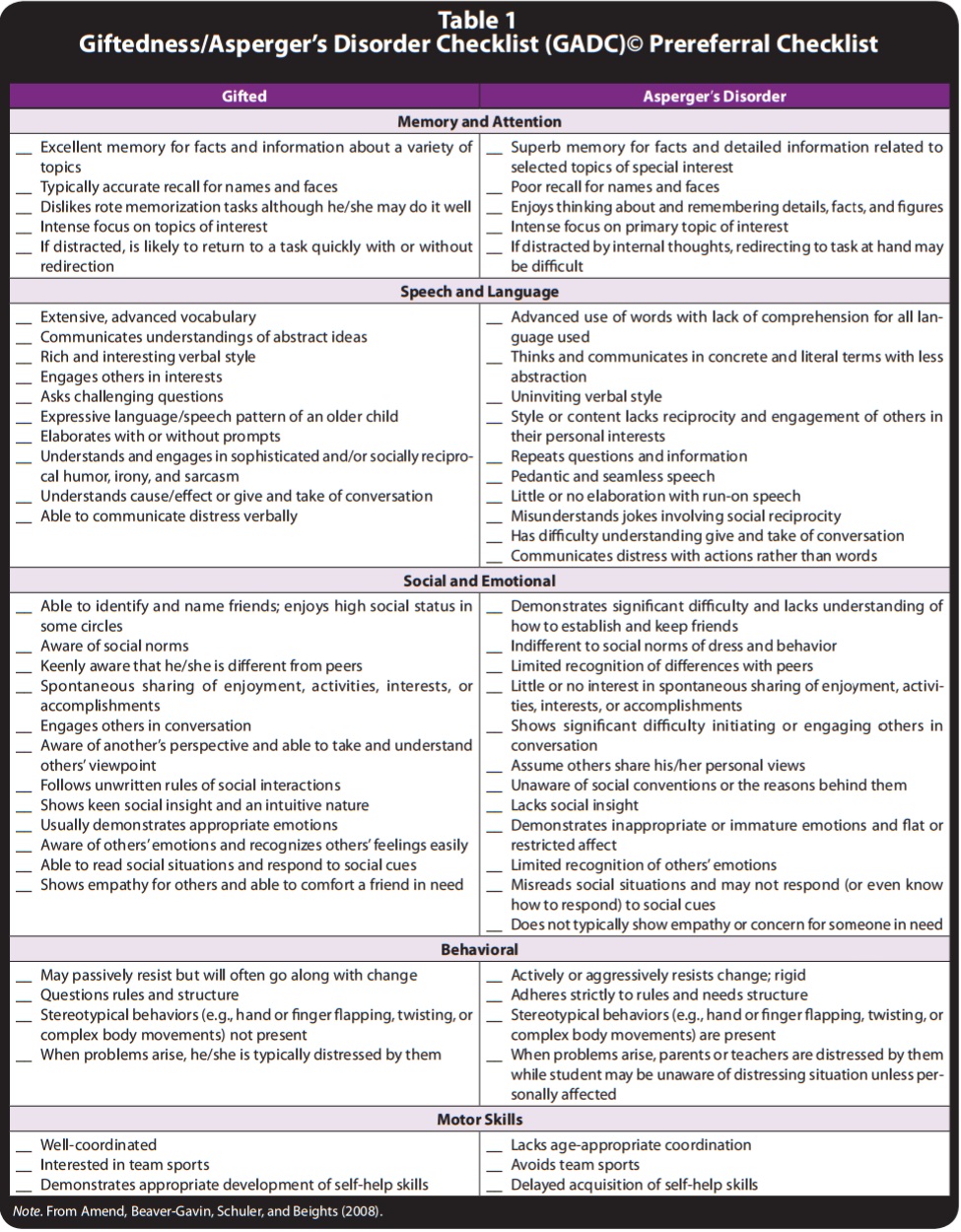

The Giftedness/Asperger’s Disorder Checklist (GADC) to be presented here was similarly developed to help educators, mental health professionals, and parents during the prereferral process to see if environmental interventions would be beneficial in the process of determining the need for more formal diagnostic evaluation. Like the DD-Checklist, the GADC focuses on the educational and psychological needs of the student who may or may not be gifted and who may or may not have Asperger’s Disorder. To avoid unneeded or inappropriate interventions, parents and educators may want to complete the GADC in Table 1 to help them to determine which interventions (e.g., those for gifted students or those for students with Asperger’s Disorder) may be most appropriate, and to help decide whether to refer the gifted child for thorough psychological evaluation.

The GADC is a clinically developed instrument designed as a tool to help guide parents, educators, and clinicians toward possible interventions and to help them begin to determine whether an unsuitable, inflexible, or unreceptive educational environment is contributing to the child’s unusual or inappropriate behavior. Although the information contained within this checklist comes from both research and clinical experience with these populations, this checklist has not been validated or normed in any way. The GADC is designed to facilitate appropriate interventions in the prereferral stage and should never be used as a substitute for formal and comprehensive evaluation when further study is necessary to determine causes of behavior.

The GADC contains characteristics that are observed in gifted children or those exhibiting Asperger’s Disorder, and these characteristics are taken from a variety of sources (e.g., American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Attwood, 2007; Cash, 1999; Klin, Volkmar, & Sparrow, 2000; Little, 2002; Mesibov, Shea, & Adams, 2001; Neihart, 2000; Silverman & Weinfeld, 2007; Webb et al., 2005). Recent research on gifted children on the autism spectrum (Assouline, Foley Nicpon, Colangelo, & O’Brien, 2008) has presented additional empirical data on the characteristics of gifted children who have Asperger’s Disorder. Case studies also provide relevant data for identification (Amend & Schuler, 2004; Cash, 1999; McKeigue, 2008; Schuler & O’Leary, 2008).

Some of the characteristics that gifted children exhibit also are seen in children with Asperger’s Disorder (Attwood, 2007; Burger-Veltmeijer, 2008; Lovecky, 2004; Neihart, 2000; Webb et al., 2005). Although similar, the behaviors may present a bit differently and/or the motivation for the behavior may be different. The behavioral descriptors and characteristics in the GADC are intended to help differentiate between giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder. The domains or categories to be explored are listed with multiple descriptors in each domain. Because there is some overlap between giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder, some characteristics may not necessarily help to differentiate between the two groups—these are not included here.

The GADC includes general behaviors characteristic of children in each group, and it would be unlikely for all descriptors in either category to apply to one child. However, if only a select few of the characteristics listed here apply to the child in question, then it may be best to consider interventions or assessment in areas other than giftedness or Asperger’s Disorder.

Using the GADC

To use the GADC, simply mark those items that apply to the child. To determine accurate differentiation, two principles should be followed. First, observe the child’s behaviors when he is with others who have similar intellectual abilities and/or interests. Secondly, examine the child’s insight about how other people see him and his behaviors (Webb et al., 2005). If most of the checks are in the gifted column, implement curriculum modifications and differentiation strategies such as those discussed in books like Teaching Gifted Kids in the Regular Classroom (Winebrenner & Espeland, 2000), Teaching Young Gifted Children in the Regular Classroom (Smutny, Walker, & Meckstroth, 1997), or Re-Forming Gifted Education (Rogers, 2002).

If most of the checks fall on the Asperger’s side or if the responses are fairly evenly split, attempt strategies to address the specific behaviors observed (Kraus, 2004) and consider referring the child for formal evaluation to explore both giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder. In these cases, books such as Helping a Child With Nonverbal Learning Disorder or Asperger’s Disorder (Stewart, 2007), Succeeding in College With Asperger Syndrome (Harpur, Lawlor, & Fitzgerald, 2004), A Parent’s Guide to Asperger Syndrome and HighFunctioning Autism (Ozonoff, Dawson, & McPartland, 2002), and Asperger’s: What Does It Mean to Me? (Faherty, 2000) may be helpful in providing information and strategies.

Although his intellectual abilities had been identified, Joey’s experience in the private school was not positive for him because the focus remained on his social and emotional difficulties. Because his highly gifted cognitive needs were not being met, Joey’s parents chose to place him in their local public school in an attempt to find a balance that addressed both strengths and concerns. As strong advocates for their son, Joey’s parents were able to demonstrate his need for grade acceleration as well as additional subject acceleration in his strength area—mathematics. Joey’s parents provided school personnel with articles on gifted children with Asperger’s Disorder from 2e: The Twice Exceptional Newsletter as well as other resources from the gifted counselor/ consultant. Awareness, understanding, and acceptance of Joey’s giftedness made the difference in how his teachers viewed him and what educational interventions he received.

If, after the prereferral process and intervention, clinicians, parents, and teachers agree that modifying the child’s environment is not producing positive results, further evaluation should be considered. Formal diagnostic tools such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, 2000), the Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (Myles, Bock, & Simpson, 2000), the Australian Scale for Asperger’s Syndrome (Garnett & Attwood, 1995), the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (Gilliam, 2006), and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (Schopler, Reichler, & Renner, 1998) should be considered when a more comprehensive evaluation is needed. Only qualified and experienced professionals should administer these instruments.

Whether or not giftedness is thought to be involved, parents and educators should seek a qualified psychologist who has experience with both giftedness and Asperger’s Disorder. It is never appropriate to label a gifted child—or any child—with a disorder such as Asperger’s Disorder without a comprehensive evaluation to rule out other potential causes for the behaviors of concern.

Future Directions

Thus far, the GADC has been useful only in informal and prereferral processes to help determine appropriate interventions for gifted children and those thought to show characteristics of autism spectrum disorders before formal evaluation is sought. It is in this arena that there is value to the GADC at this time. Before referral for formal evaluation, much can be done to lessen the stress, improve the academic performance, and enhance the social and emotional development of children who demonstrate behaviors that resemble those along the autism spectrum. The GADC is a step toward identifying the category of interventions that may be beneficial for a particular child who may or may not be gifted, or may or may not have Asperger’s Disorder. The authors, who primarily work in private and/or school-related facilities, have not formally evaluated the reliability and validity of the GADC. They encourage researchers to explore its usefulness in order to increase the utility of the GADC and its impact on gifted or twice-exceptional youth. The authors firmly believe that using the GADC in the prereferral stage will lead to fewer inappropriate referrals and referrals that are more carefully screened, provide direction regarding appropriate intervention, and increase the likelihood that giftedness, rather than pathology, might be explored as an hypothesis for the behaviors in question.

References

Amend, E. R., Beaver-Gavin, K., Schuler, P., & Beights, R. (2008). Giftedness/ Asperger’s Disorder Checklist (GADC) Pre-Referral Checklist. (Available from Amend Psychological Services, PSC, 1025 Dove Run Road, Suite 304, Lexington, KY 40502)

Amend, E., & Schuler, P. (2004, July). Challenges for gifted children with Asperger’s Disorder. Paper presented at the annual meeting of Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted (SENG), Crystal City, VA.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Assouline, S. G., Foley Nicpon, M., Colangelo, N., & O’Brien, M. (2008). The paradox of giftedness and autism: Packet of information for professionals (PIP)—Revised. Iowa City: The University of Iowa, The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Attwood, T. (2007). The complete guide to Asperger’s syndrome. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Bashe, P. R., & Kirby, B. L. (2001). The OASIS guide to Asperger syndrome: Advice, support, insight, and inspiration. New York: Crown.

Baum, S. M., & Owen, S. V. (2004). To be gifted & learning disabled: Strategies for helping bright students with LD, ADHD, and more. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Boland, C. M., & Gross, M. U. M. (2007). Counseling highly gifted children and adolescents. In S. Mendaglio & J. S. Peterson (Eds.), Models of counseling gifted children, adolescents, and young adults (pp. 153–197). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Burger-Veltmeijer, A. (2008, September). Giftedness and autism: From differential diagnosis to needs-based assessment. Paper presented at the European Council for High Ability (ECHA) Conference, Prague, Czech Republic.

Cash, A. B. (1999). Autism: The silent mask. In A. Y. Baldwin & W. Vialle (Eds.), The many faces of giftedness: Lifting the masks (pp. 209–238). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Cross, T. (2004). On the social and emotional lives of gifted children: Issues and factors in their psychological development (2nd ed.). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Eide, B., & Eide, F. (2006). The mislabeled child: How understanding your child’s unique learning style can open the door to success. New York: Hyperion.

Faherty, C. (2000). Asperger’s: What does it mean to me? Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.

Garnett, M. S., & Attwood, A. J. (1995). The Australian Scale for Asperger’s Syndrome. In T. Attwood (Ed.), Asperger’s syndrome: A guide for parents and professionals (pp. 16–20). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Gilliam, J. E. (2006). Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS-2). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Grandin, T., & Duffy, K. (2004). Developing talents: Careers for individuals with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishers.

Harpur, J., Lawlor, M., & Fitzgerald, M. (2004). Succeeding in college with Asperger Syndrome. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.Hartnett, D. N., Nelson, J. M., & Rinn, A. N. (2004). Gifted or ADHD? The possibilities of misdiagnosis. Roeper Review, 26, 73–76.

Klin, A., Volkmar, F. R., & Sparrow, S. S. (Eds.). (2000). Asperger’s syndrome. New York: Guilford Press.

Kraus, S. (2004, October). Asperger’s and beyond: Strategies that work for educators and parents. 2e Twice Exceptional Newsletter, 7, 4–5, 19.

Little, C. (2002, Winter). Which is it? Asperger’s syndrome or giftedness? Defining the difference. Gifted Child Today, 25(1), 58–63.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., & Risi, P. (2000). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Lovecky, D. V. (2004). Different minds: Gifted children with AD/HD, Asperger Syndrome, and other learning deficits. London: Jessica Kingsley.

McKeigue, L. (2008, September). An investigation into the experiences and perspectives of exceptionally able children with Asperger’s syndrome attending Irish primary schools. Paper presented at the European Council for High Ability (ECHA) conference, Prague, Czech Republic.

Mesibov, G. B., Shea, V., & Adams, L. W. (2001). Understanding Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Myles, B. S., Bock, S. J., & Simpson, R. L. (2000). Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Neihart, M. (2000). Gifted children with Asperger’s Syndrome. Gifted Child Quarterly, 44, 222–230.

Ozonoff, S., Dawson, G., & McPartland, J. (2002). A parent’s guide to Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: How to meet the challenges and help your child thrive. New York: Guilford Press.

Rogers, K. B. (2002). Re-forming gifted education: Matching the program to the child. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Rogers, K. B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51, 382–396.

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1998). Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Bloomington, MN: American Guidance Services.

Schuler, P., & O’Leary, N. (2008, September). Gifted students with Asperger syndrome: Case studies. Paper presented at the European Council for High Ability (ECHA) Conference, Prague, Czech Republic.

Silverman, S., & Weinfeld, R. (2007). School success for kids with Asperger’s syndrome. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Smutny, J. F., Walker, S. Y., & Meckstroth, E. A. (1997). Teaching young gifted children in the regular classroom: Identifying, nurturing, and challenging ages 4–9. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Stewart, K. (2007). Helping a child with nonverbal learning disorder or Asperger’s disorder (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Webb, J. T., Amend, E. R., Webb, N., Goerss, J., Beljan, P., & Olenchak, F. R. (2005). Misdiagnosis and dual diagnoses of gifted children and adults: ADHD, bipolar, OCD, Asperger’s, depression, and other disorders. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Winebrenner, S., & Espeland, P. (2000). Teaching gifted kids in the regular classroom: Strategies and techniques every teacher can use to meet the academic needs of the gifted and talented (Rev. ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Permission Statement

Comments

Ida

Steph Jones